Introduction...

Dear Emmanuel,

You are 16 years old, and now is a good time to be thinking about what sort of life you would want to live. Now, I don't know what the best choices are for you, and you probably don't, either, and hopefully you'll keep learning and trading in your plans for better plans as time passes. So I don't have a roadmap to offer you, but I do think it might be educational, or maybe just entertaining, to do a little bit of math to illustrate some of the options you have to choose from.

You are 16, and when it comes to life expectancy, you are coming into the game with the slight disadvantage of being male. The actuaries of Social Security have produced some tables which indicate that you have 61 years of life expectancy left -- in other words, given the (doubtful) assumption that death rates for all ages stay the same from here on out, the median lifespan for boys your age will stretch to 77 years. But you could easily die before or after that time (the year 2073), and so if you are drawing up plans, it's safest to assume you'll live longer. If you live shorter, no problem. You're dead, and you don't have to worry about it. But it would be embarassing to, say, pile up a bunch of money for to last till you're 77 and then suddenly find yourself run out at 78.

So instead of looking at the median, the 50th percentile, perhaps we'd be better off looking at something like the 95th percentile of lives. By that standard, you would want to plan to live to 96. Maybe you should plan to live even longer, but we don't need to get into that yet. Once we've run through a few mathematical exercises, it will become clear that planning to live to 100 or even 120 or 200 is in principle not much harder than planning for 77 or 96 years.

Two Questions...

There are a lot of questions we all must ask ourselves in life, but here's two to start with:

Do I want to work for a living until I die?

And if not,

How much of my life do I want to spend in a position where I need to work to make a living?

Two Simple Scenarios...

I am not going to give you answers to those questions, but just some math exercises to help look at your options. To make our math simple, let's imagine your earnings are steady over time, and you have to retire based on your savings. Let's ignore the fact that both of these assumptions are false for now. Hopefully once we've done a lot more math, it'll be clear why we made these assumptions. Let's also assume that from 16 to 18, you get to live off your parents.

So you need to account, now, for living from 18 to 96: that's 78 years of life. The simplest plan is no plan at all -- just spend all the money you make, and just work till you die, or till you become too frail to work. At that point, hopefully the taxpayers or somebody else will feel sorry for you and keep you alive. That's the zero-savings option.

Another option is to save half your money. For now, let's pretend that inflation doesn't exist (or your savings are somehow secured against it) and that beyond beating inflation you are earning no interest. In this scenario, every year you spend half you money, and you save an equal amount. Another way to think about it is that in this scenario, you are saving 1 year worth of expenses every year.

If you do this from 18 onward, when you're 28, you'll have 10 years worth of expenses stored up. When you're 38, you'll have 20 years worth of expenses stored up. When you're 48, you'll have 30 years worth of expenses stored up. When you're 57, you'll have 39 years of expenses stored up. Now you can retire and life off your savings till you're 96. So this is our first retirement savings scenario.

A Word about the Word 'Retire'...

There is a common idea that, when you retire, you are magically transported to Florida, where you will spend your days golfing, drinking, and watching television, earning no income, until you die. This is one option for how you can retire. But I'd like to use the word 'retire' in a broader sense. For the purpose of our math here, you are 'retired' when you no longer need to work to pay your expenses. You can then work if you feel like it, volunteer to raise stranded baby sea otters, or anything else. But at this point, you own your time.

Retirement, at least the kind I'm thinking of, simply means reaching the point where the threat of running out of money does not dictate how you spend your time. So if the thing you want to do most in that state is drink and golf in Florida, that's fine. If you want to build houses for fun, that's also fine. If you want to pretend you're not retired and just work in a cubicle somewhere, that's cool too. The important thing here is that you're now free to leave whenever you want. You are not financially locked into the working world.

Introducing Returns on Investment...

In our first retirement scenario, you save half your money from age 18 on, you retire at 57, and then you go do whatever you want for the rest of your life. The good news here is that returns on investment change this situation quite a bit.

Now, returns on investment are impossible to predict, exactly, but there is a long historical record of what happens if you invest broadly in the market: since the late 1800's, when the modern stock market was born, average stock investments tend to grow at about 7% per year above inflation. This means that, if you invest your money in a way that yields average returns, you actually save money quite a bit faster than our first scenario predicted.

So now let's try a second retirement scenario. In this scenario, you save half your income, continuously, as you make it throughout the year. Just to make the math easier, let's say that throughout the year, you plunk it into a savings account earning 0%, and then transfer it to investments at the end of each year. It starts earning you 7% interest each year. We can then watch your retirement nest egg grow in this handy chart:

| Year of saving | Total nest egg at the end of the year |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2.07 |

| 3 | 3.21 |

| 4 | 4.43 |

| 5 | 5.76 |

| 6 | 7.15 |

| 7 | 8.64 |

| 8 | 10.25 |

| 9 | 11.97 |

| 10 | 13.81 |

| 11 | 15.76 |

So at the end of eleven years, you have saved 15.76 years worth of expenses -- basically, 11 years of that you saved directly, and 4.76 years worth was added by ordinary market returns. This is where things get really interesting. If you have 15.76 years of income saved, and it earns a return of 7%, then the return on your investments in the next year will equal 1.1 years worth of living expenses. And it will keep producing more than 1 year of living expenses forever, so that you can live off it indefinitely.

In other words, you have now escaped needing to work to pay your expenses. You started at 18, and you finished at 29. You are now retired. This is our second retirement scenario. By introducing simply average returns on investment, we have cut your working life from 18-57 down to 18-29. That's 28 years of your life added just by average stock returns.

Introducing Turbulence...

Unfortunately, our second retirement scenario, where you earned average returns and worked 11 years, suffers from a fatal flaw -- average is just the average market returns, so about half the time the market performs above average, and half the time below average. You could find that you retire right before a stock market crash, and then you suddenly do not have enough money to pay your expenses, then you eventually draw down your entire savings and have to work again.

It is possible to mitigate this risk. In our simplified scenario (2), we imagined that the market produces 7% returns every year, so you can withdraw 7% of your savings every year indefinitely. In that toy example, 7% is our "safe withdrawal rate". But the actual safe withdrawal rate requires knowing the future, which is very hard. While we don't know the future, we do know quite a bit about the past, so we can look backward and see what safe withdrawal rates would have been in any of a variety of years.

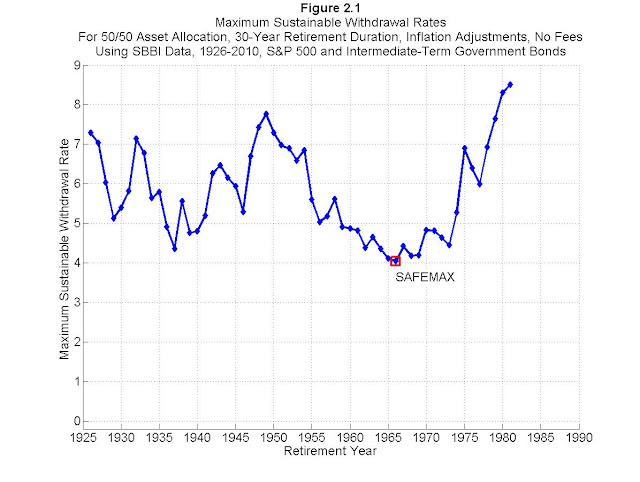

Now, the math behind this is interesting, and if you want to go deeper into it, you can start here and follow the links in that article further. It's an article by a blogger who calls himself Mr. Money Mustache, who is where I learned a lot of the basic mathematical ideas I'm writing about now. He includes a little chart by Wade Pfau, which shows what the maximum sustainable withdrawal rate would have been for a variety of years in the past, from 1926 to 1981.

In other words, the actual safe withdrawal rate in the past has varied from about 4% to about 8.5%. Of course, the future could always be better or worse, and there's also a variety of interesting mathematical complications that went into exactly what Wade Pfau and Mr. Money Mustache are talking about, but let's just borrow that 4% number for now, even though it may not be exactly right, and let's assume that

In other words, the actual safe withdrawal rate in the past has varied from about 4% to about 8.5%. Of course, the future could always be better or worse, and there's also a variety of interesting mathematical complications that went into exactly what Wade Pfau and Mr. Money Mustache are talking about, but let's just borrow that 4% number for now, even though it may not be exactly right, and let's assume that

4% is probably a safe withdrawal rate for most people

Remember, if for some reason you hit all kinds of bad luck, you can still go back to work for a while and top off your savings, and when you get old enough the government will start sending you cash, which we haven't been using in our calculations, so the small chance 4% isn't "safe" still may not be too much to worry about.

Scenario 3...

So, for our third scenario, let's say that instead of just saving till you hit 15 years worth of expenses, you save until you have 25 years of expenses. That just means we need to fill out the chart from scenario (2) a little more.

| Year of saving | Total nest egg at the end of the year |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2.07 |

| 3 | 3.21 |

| 4 | 4.43 |

| 5 | 5.76 |

| 6 | 7.15 |

| 7 | 8.64 |

| 8 | 10.25 |

| 9 | 11.97 |

| 10 | 13.81 |

| 11 | 15.76 |

| 12 | 17.86 |

| 13 | 20.11 |

| 14 | 22.52 |

| 15 | 25.10 |

So now, in our third scenario, you have to work 15 years to retire. So if you start at 18, you work to 33, and then you get to retire till 96.

A Bunch More Scenarios...

The next thing we might want to do is to fiddle with the savings rates and see what happens to how long we must work for retirement. But we don't want to build tons of charts. Thankfully, there is a way to automate this. A few paragraphs ago I mentioned Mr. Money Mustache, a guy who 'retired' in I think ten years, if I remember right, and then wrote a bunch about the math behind it. He's since been in various kinds of business, so maybe 'retired' isn't the right word, but he achieved 'retirement' in our broader sense of no longer needing to work to support his lifestyle.

Another writer I learned more from is the even more hardcore Jacob Lund Fisker, the author of the Early Retirement Extreme blog and a book by the same name. I think it was Fisker where I found a link to a nifty online calculator:

That calculator will automatically generate charts for you if you input your assumptions: annual income, annual savings, annual expenses, savings rate, return on investment rate, and withdrawal rate. For now, let's use 7% for return on investment (average stock returns) and 4% for our withdrawal rate. We'll keep those steady and move around the percent saved to see how long it takes to retire:

| Percent Saved | Years to Retirement |

|---|---|

| 0% | Work forever! |

| 5% | 52.2 |

| 10% | 41.75 |

| 15% | 35.3 |

| 20% | 30.7 |

| 25 % | 27.1 |

| 30% | 24.0 |

| 35 % | 21.4 |

| 40% | 19 |

| 45% | 16.9 |

| 50% | 15.0 |

| 55% | 13.1 |

| 60% | 11.4 |

| 65% | 9.8 |

| 70% | 8.3 |

| 75% | 6.8 |

| 80% | 5.4 |

| 85% | 4 |

| 90% | 2.6 |

| 95% | 1.3 |

| 100% | Just retire now. Your lifestyle requires no money. |

If you play with the numbers a bit, you will notice something.

How long it takes to retire depends on your savings rate, but not on total income beyond that.

So for example, if you make $50,000 per year and live on $25,000, a 50% savings rate, after 15 years you will have 650,213 saved up, which is what you need to withdraw $25,000 per year. On the other hand, if you make $100,000 per year and live on $50,000, also a savings rate, after 15 years you will have 1,300,428 saved up, which is what you need to withdraw $50,000 per year.

You can fiddle around with the numbers as much as you like, and you'll see that this holds true: it's the ratio of expenses to savings that matters, not the absolute size of either. And this leads us to another, extremely important principle.

A Penny Saved is More than a Penny Earned...

Let's start with a scenario where you make $50,000 per year and save $25,000, which will require you to work 15 years. Now let's say you want to lower that to 9.8 years of work. According to the chart above, you need to get your savings rate up from 50% to 65%.

There are, mathematically, two ways you can do that. One is to find ways to cut your living expenses further. If you can live off 35% of your $50,000 in income, or $17,500, you've hit the 35% target. That requires reducing your expenditures by $7,500. Maybe this involves a cheaper car, a roommate, and/or less eating out.

The other thing you can do is increase your income, until the 25,000 you live off is just 35% of your total income. So you take 25,000, multiply by 100, and divide by 35. To do this, you need an income of $71,429 per year, that is, you need to increase your income by $21,428 per year.

In other words, you can buy your way out of five years of working, in this scenario, by either cutting $7,500 from your budget, or by making $21,428 dollars more: a penny saved is worth almost three pennies earned. And if you want to think intuitively about that, the basic reason is that when you lower your expenses, you are both growing your savings, but simultaneously lowering the goal you need to hit to be financially independent.

Closing Thoughts...

Let's talk another scenario. The American "poverty line", according to the Federal Government, is $13,590 per year, or 1132 per month. I am quite confident that you could live on that. It's possible to rent a room in Lima for about $400 per month -- probably less -- and then $200 would cover groceries, another $200 should cover car expenses if you're careful, and then that leaves you with $300 for miscellaneous. It's doable.

It's also doable to make $40,000 per year, after taxes, in a factory. That gives you a savings rate of 65% -- retirement in ten years. And if you look for it, there's probably ways to make money in your off hours, and ways to cut expenses still further: living with more roommates or family, riding a bike, adopting a diet based on rice and beans and green vegetables. If you hustle, I would not be surprised if you could kick the savings rate up to 75%.

If you saved 75% from age 18 to age 25, you could retire. Of course, you don't want to sit still for the next forty years. You could keep working and get rich. You could spend ten years obsessing over peppers without making a dime. You could do all manner of things, without worrying about how you're going to keep a roof over your head and food on your plate. You could change your projects every few years and dip in and out of different jobs and projects, never having to worry about whether they can support you.

You could be financially independent by the age when many of your peers are finishing college.

I'm not saying you should do this. Maybe you'd like to get married, and maybe the woman you'd want to marry doesn't want to be poor. Maybe you want to raise children, and they cost money. There's many good reasons to save like an extremist and retire, and there's many good reasons not to.

But at least, now that we've toured some of the basic math, I hope you understand that you have an enormous range of options in front of you, including everything from financial independence at 25 years old all the way out to working your entire adult life, and everything in between.